Hello, gentle readers. It’s been a while. I’m almost afraid to check on the date of my last post here. But I’m still alive, and quite well, although a number of things have changed.

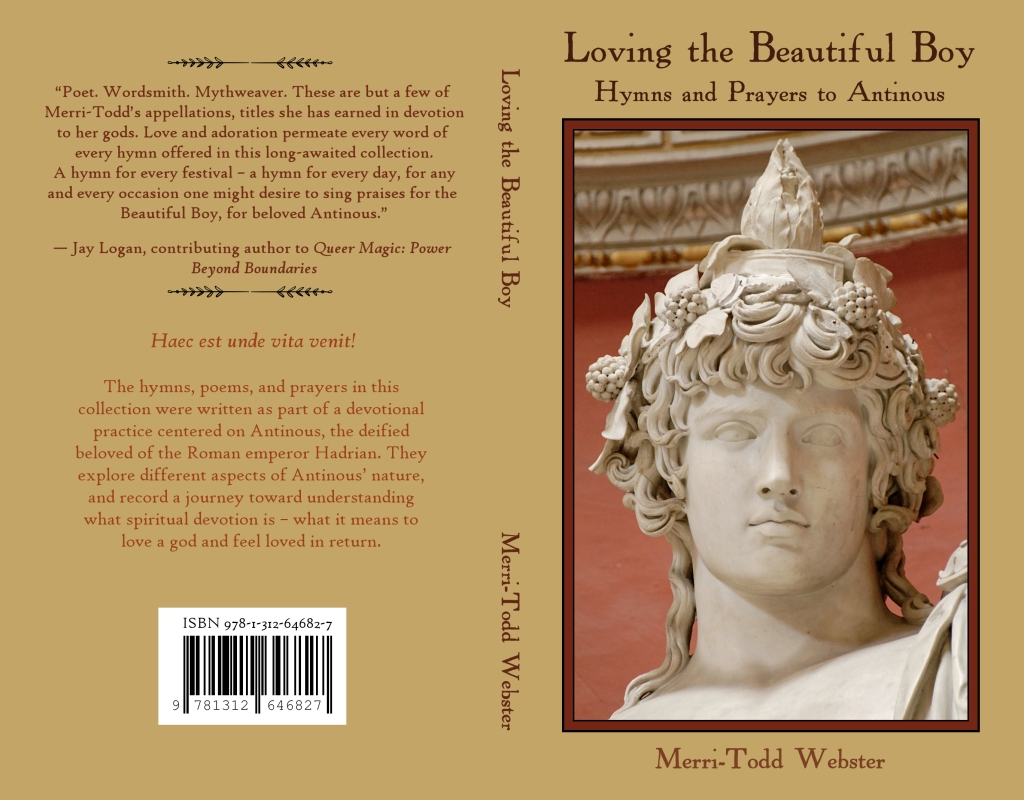

First I’d like to remind you that I published a book! Loving the Beautiful Boy: Hymns and Prayers to Antinous is available in print from Lulu.

Second, I’d like to announce that Loving the Beautiful Boy is also available in Amazon Kindle format! Get your ebook copy today and for Antinous’ sake, write me a favorable review. *g*

I don’t think I have written here about my bird companion Sunny. In October 2021, my dear bird Rembrandt died at the age of about twenty-three, having been with me for twenty-one years. I was honestly devastated, even though it was not entirely a shock; I knew he was old, and he had been visibly slowing down. Months went by before I could even dispose of his empty cage.

I had been without any birds for a little over a year, for the first time in nearly thirty years, when a chance conversation with a co-worker led to her rehoming with me a little lutino cockatiel named Sunny, whom she had taken in five years earlier when his first owner died. In that time he had lived with five cats and at least one dog, not at all a comfortable situation. When I was introduced to him, I offered him my hand, and this bird who rarely came out of his cage immediately stepped onto my finger and began telling me his life story. I have now had him for about eighteen months and he is my spoiled only child. Right now he is snoozing in the afternoon sun.

Over the past few years I have engaged with blogging less and less, not only as a writer, but as a reader; most of my writing has been fanfiction, which you can find here at AO3. Due to the rise of so-called AI, I have locked most of my archive to registered users, but the most recent couple of stories will always be readable by guests as well, and there will never be any monetization of my fanfic.

I have, however, just recently started writing a newsletter through Buttondown, a fairly new service that I am so far pleased with: A Letter from Saskia. I have been writing about Sunny, about my reading, about what’s happening on the spiritual front, and whatever else crosses my mind. With this in mind, I am planning to delete this blog sometime this year. I will make a further announcement about that when I have set a date.

I wish a blessed Holy Week and Easter, Ramadan, Ostara, Purim, or whatever else one might be celebrating to all my readers, and hope to see you as subscribers to my newsletter. Love to all.